Is the credibility of the LFS at stake?

The credibility of the LFS ia at stake only if you believe it can precisely measure monthly movements to the decimal point. Jay Bryan of the Montreal Gazette said Statistics Canada had to explain Quebec’s fourth-quarter job slump to keep its credibility. That won’t happen, because no explanation is possible. Of course it was not plausible that Quebec’s economy was contracting late in 2011 at a faster rate than during the worst of the 2008-2009 recession. But it is also incumbent on users to treat the estimates for what they are—estimates, with sizeable standard errors around them.

The credibility of the LFS ia at stake only if you believe it can precisely measure monthly movements to the decimal point. Jay Bryan of the Montreal Gazette said Statistics Canada had to explain Quebec’s fourth-quarter job slump to keep its credibility. That won’t happen, because no explanation is possible. Of course it was not plausible that Quebec’s economy was contracting late in 2011 at a faster rate than during the worst of the 2008-2009 recession. But it is also incumbent on users to treat the estimates for what they are—estimates, with sizeable standard errors around them.

As we already noted, there is nothing unusual about Quebec’s (or any other province’s) data diverging from the national trend for several months. Nor does this detract from the accuracy of the LFS estimates at the national level. They are highly accurate, as shown by their very small revisions every 5 years when they are benchmarked to the employment estimates from the Census. They are so accurate that I use them to help identify turning points in the economy as it moves into and out of recessions. Inevitably, however, as you drill down from the aggregate employment data to the industry and provincial detail, the relative importance of noise in the estimates rises.

Statistics Canada does not help by downplaying the variability of the estimates. For example, the published standard errors surrounding the monthly LFS estimates are a theoretical calculation derived from relating the sample size used in the survey to what a census would yield.

For Quebec employment, the standard error is 20,000; for example, the October drop of 14,000 means that StatCan is 68% confident that employment actually moved within a range of a 34,000 drop to a 6,000 increase; at a 90% level of confidence, the range expands from a drop of 48,000 to an increase of 18,000. At 95%, which is probably a level most analysts feel comfortable with when analyzing data movements to the percentage point, the range is from a 54,000 drop to a 26,000 increase, which is tantamount to saying they are not even sure about the first digit to the left of the decimal point, never mind to the right of it. Most analysts are not aware that this data comes with such large confidence intervals, but these values are taken from StatCan’s 2011 Guide to the Labour Force Survey. [1] Another example of this variability is employment in the finance industry: after inexplicably falling by 75,000 over the previous six months, it suddenly jumped by 41,000 in February.

Revisions due to seasonal factors

Moreover, in the real world where analysts live and comment, there are other sources of revisions that users have to contend with that are not captured in these published standard error rates. The most obvious example is revisions to the seasonal factors, which can be significant. For example, the preliminary data for October and November 2010 showed Canada-wide employment stalled with no growth in the former and just a 0.1% gain in the latter, leading to a great deal of consternation in the chattering classes. The latest estimates show growth of 0.2% in October and 0.1% in November, which leaves a much different impression of an economy growing steadily rather than stalling.[2]

October in particular has proven to be a difficult month to estimate; the estimate for October 2009 was revised from a 0.3% decline to no change. Given the upward revisions to the recent October preliminary estimates resulting from new seasonal patterns, the real confidence interval around the October estimate is probably something close to -40,00 to +30,000, given the pronounced trend recently to upward revisions in October . And that is only at the 68% level of confidence. Given the large uncertainty around monthly movements, why would you let the decline of 14,00 jobs published for Quebec for October 2011 unduly influence your view of the economy, particularly when it flies in the face of every other indicator? The true standard error for November covers a smaller range than October, since this month has had only very small revisions to its seasonal factor.[3]

This lack of attention to revisions is widespread in Statistics Canada. In 24 years of editing the Canadian Economic Observer, the only articles I ever saw on revisions came from Income and Expenditure Accounts (the quarterly GDP people), who have always maintained an extensive database on revisions since before I entered the Agency in the late 1970s, as well as Investment and Capital Stock Division, which maintains the annual survey of investment intentions. It may just be a coincidence, but these are also two of the datasets that I follow the most. Users would be better served, and Statistics Canada would do a better job of monitoring its own data quality, if more divisions maintained a record of their revisions and analyzed it to judge where their weaknesses are.

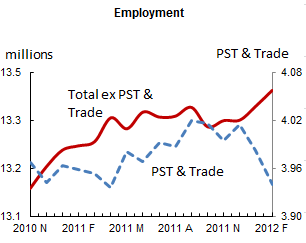

As noted last month in this newsletter, the monthly estimates for Quebec quite regularly diverge from the trend of the Canadian economy for lengthy periods, only to revert to the Canadian trend. This is especially true when the other major data series for Quebec show no signs of the weakness in the employment data. However, the gap between retail sales in Quebec and employment was exaggerated in the fourth quarter of 2011 as a result of the impending hike to the provincial HST on January 1, 2012. In response, sales in Quebec surged 2.1%, above the national average despite the slowdown in jobs. It is worth recalling that sales in Quebec jumped 2.9% in the fourth quarter of 2010, just before another hike in the sales tax, but sales then fell 0.9% in the first quarter of 2011. One would expect a similar softening of sales in Quebec early in 2012. This expected weakness in retail sales in Quebec early in the year would explain why its trade employment fell sharply in February.

[1] Catalogue no 71-543-G, p 25 thru 27.

[2] It might be argued that seasonal factors were not the only source of revisions between 2009 and 2012, since the LFS was benchmarked to the Census employment estimates early in 2011. But since these revisions lowered employment slightly over the five years, they cannot be the source of the upward revision to October and November.

[3] January has had the largest revisions of any month since 2006, and all of them downward, but this may just be a function of the step adjustment needed to lower the estimates to meet the census revision more than a new seasonal pattern. Front-loading these declines into January minimizes the revisions to the rest of the year.