The Bay Street Buck Oped

This is a comment to the oped I wrote in the National Post on March 7 2012. The motivation was the response to comments by Premier McGuinty that the oilsands had driven up the exchange rate and this was harming Ontario’s manufacturing industry. Lots of people pointed out the superficial analysis connecting the exchange rate and problems in manufacturing. What alarmed me was how quickly many level-headed people were prepared to accept the first assertion, that the dollar was being driven up by oil prices. I have seen before where the public debate over an issue can quickly go off the rails because of a basic misunderstanding of the facts (cross-border shopping as the loonie first approached partity with the US dollar in 2007 comes to mind), and if not immediately challenged, quickly solidifies and poisons the public debate for years. Other recent examples of this phenomenon of a falsehood being repeated so quickly and widely that it becomes a ‘fact’ underpinning public debate include the notions that living standards are falling or that manufacturing in this country is doomed. I will address both in forthcoming newsletters.

But for now, I wanted to challenge the idea that oil prices were driving the dollar. I have written extensively on the growing importance of resources in our economy over the last decade. But an analysis of the logic behind why natural resources, and especially just one type of resource, would drive the dollar quickly exposes the flaw. Trade flows do not determine the exchange rate; if they did, why is the dollar at parity with the US greenback, where it was just before the 2008 recession, while over the same period our current account balance has gone from a record surplus of $5.7 billion early in 2008 to a deficit of $10.3 billion in the fourth quarter of 2011? How did the US maintain a strong dollar policy during the 2000s while running record trade deficits. Japan has struggled with a rising exchange rate this year, even as it posted its first trade deficit in years. Anyway, enjoy the oped, for which I kept the original title.

The Loonie: Petro-dollar or the Bay St Buck?

The debate triggered by Premier McGuinty’s comments about the impact of the oilsands on raising the exchange rate and the impact of the stronger loonie on manufacturing has focused on the question of whether Ontario’s manufacturing base is suffering from a high exchange rate, or is facing problems common to all manufacturers around the world.

The premise seems to be accepted that oil prices are driving the exchange rate: the loonie is now perceived as a ‘petro-currency’ by many.

Before this becomes another orthodoxy in public discussions about our economy, let’s consider another feature of our economy that has been increasingly attractive to people outside of Canada in recent years: our financial system.

Canada’s banking system is easily the soundest in the G20 group of nations, having emerged virtually unscathed from the financial crisis that crippled the US in 2008 and which continues to affect Europe into 2012. In the midst of this financial turmoil, Canada’s financial system stands out as a safe haven. Of course, our financial system is concentrated in Toronto, one reason a recent report by Moody’s Analytics projected its financial services industry would soon surpass London’s.

This probity has not gone unnoticed on the international stage. The Bank of Canada’s Mark Carney was recently appointed head of the Financial Stability Board, which draws up the rules for international banking. Toronto is now home to the newly created Global Risk Institute in Financial Services. Iceland is even talking about adopting the loonie as its currency.

Bond investors certainly have treated Canada as a safe haven since 2008. While their initial response in any crisis is to buy US Treasuries, since 2009 they have snapped up $224 billion of bonds in Canada, one-third more than our total exports of crude oil over the last three years.

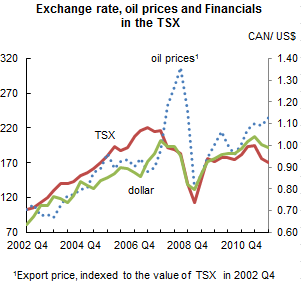

The graph below shows the quarterly relationship between the exchange rate and the Financial component of the TSX. The fit is at least as good as for the export price we received for our oil, especially after the onset of the financial crisis in 2008.

The positive impact of a robust banking system is felt beyond the financial sector. At least some of the boom in condo construction in downtown Toronto reflects demand from overseas investors, who naturally want to have a place close to where their money is safely parked.

So there is a second, competing narrative for the recent strength of the Canadian dollar. Instead of focusing on oil exports from northern Alberta, this story centres on Bay Street. I doubt we’ll hear anyone at Queen’s Park decry the stability of our financial institutions, but don’t think for a minute that they have not been a major contributing factor to the high exchange rate. The Ontario government has even run advertisements touting “The World’s Soundest Banking System is Headquartered in Ontario, Canada”.

If you’ve got the world’s soundest banking system, don’t be surprised if you’ve also got one of the world’s strongest currencies. Alberta premier Alison Redford might want to point that out the next time Mr. McGuinty lectures us on economics.