Business Investment: the driving force of economic growth

|

The recent release of the annual survey of business investment is, for me, among the most important data releases from Statistics Canada. If eyes are the window to the soul for humans, then investment is the window to understanding what firms are thinking, not just this year, but their plans for the future. After going into the industry patterns of investment in more detail, this newsletter concludes with a brief summary of why business investment is the key to analyzing the economy. |

To judge by the results for 2012, firms remain quite optimistic about the prospects for sustained growth. Actually, in the resource sector, firms seem ecstatic, with investment at levels well beyond anything seen before in Canada. Investment in manufacturing also is at an historically high level, belying the pessimism of analysts outside of this sector. The only significant decline in investment was in our much-vaunted financial sector, notably banks, after splurging on outlays last year.

Overall, firms plan to invest $233.9 billion in new plant and equipment in 2012, an increase of $19.0 billion or 8.8% above 2011.[1] Firms raised investment by about 12% in both 2010 and 2011 coming out of the recession.[2] The 2012 final result is likely to be above 10%, since the track record has been for firms to adjust spending upwards as the year progresses. This trend to upward revisions could be quite pronounced for 2012, given that the gloom and uncertainty about the global economy last autumn was dissipating rapidly early in the new year, and the Quebec and federal governments moves to encourage investment in energy and mining.

Energy and mining dominate investment…

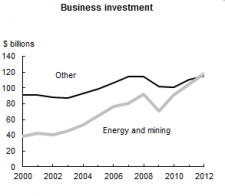

Of the $19 billion increase in investment plans for 2012, over $18 billion originated in just two sectors: energy and mining. Energy, which includes oil and gas, utilities, pipelines and petroleum refining, anticipates a $14.1 billion increase. Mining outside of oil and gas intends to boost investment by $3.2 billion. Including primary metals, which is mostly the smelting and refining of metals, adds another $1.1 billion.

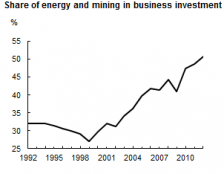

For the first time ever, over half of all business investment is directed to energy and mining. In terms of the share of total investment, energy and mining account for 50.7% of investment in 2012, up from barely one-quarter (27.0%) in 2002. By itself, energy accounted for 42.3% of investment plans in 2012 and mining 8.4%. Adding in the primary sectors of agriculture, fishing and forestry and manufacturers of forestry products lifts the total share of natural resources in investment to 56.5%.

Energy

Energy has been the leading force behind this marked shift to investment in natural resources. Utilities and the oilsands have contributed almost equally to the increase in energy, rising from less than $10 billion in 2000 to just over $25 billion in 2012. While the oilsands are exclusively in Alberta, the increase in utilities has been spread across Canada.

Capital spending for conventional oil and gas peaked at $36.1 billion in 2006. It then declined for three straight years to about $20.2 billion, the result of dwindling supplies of conventional oil and falling energy prices during the recession. However, since their low in 2009, investment in this sector has nearly doubled, reaching a record $37.2 billion in 2012. This increase is all the more impressive in light of the huge drop in the price of natural gas prices that began in the recession and has continued since, the product of new drilling techniques for shale gas. The fact that the $17.0 billion increase in investment spending for conventional oil and gas since 2009 exceeds the $16.3 billion surge for the oilsands is a testament to how technology has changed the exploration and development of natural gas.

It is a major oversight that, while Statistics Canada has data on oilsands, it has no comparable classification for unconventional natural gas sources. This is the type of thing that frustrates users of data. By comparison, Statcan not only publishes data for investment in the coal industry, but lists 3 subcomponents: bituminous coal, subbituminous coal, and lignite coal. But of the 42 cells for this data, 37 are suppressed for confidentiality, and 2 others have 0 values (i.e. there was no investment). So Statcan maintains this rich level of detail for coal, whichcontains essentially no data, while ignoring the development of a new industry that involves tens of billions of dollars and that is literally changing the face of the gas industry. Only a government bureaucracy could produce such a result.

Mining shatters records

While energy has been the most consistent source of growth in resource investment over the past decade, mining has increasingly taken the lead in recent years. From a low of barely $2 billion at the turn of the century (not enough even to offset depreciation, leading to an erosion of the capital stock in this industry), capital spending in mining rose steadily to $8.6 billion, before retreating during the recession to $7.1 billion in 2009. However, growth since the recession has been on a lunar trajectory, more than doubling in just three years to $16 billion in 2012. In fact, the $8.6 billion increase in the level of investment in mining over the last three years equals the peak level of all mining investment reached in 2008.

The source of the boom in mining has been quite diverse, reflecting the widespread advance in prices. For 2012, gold lead the way with $3.6 billion of capital spending. But not far behind were copper-nickel-zinc mines at $3.0 billion, potash at $2.9 billion and iron ore at $2.7 billion as the Labrador Trough is developed. Needless to say, investment in all these industries shatters their previous records back to 1991, often by a multiple of ten or more. It is noteworthy that despite this decade-long surge in investment, production of most of these metals remains well below their levels of a decade-ago, a reflection of how it takes ever-increasing amounts of inputs to extract a dwindling supply of metals output.

Manufacturers show confidence in growth

Manufacturers plan to invest $20.3 billion in 2012, essentially returning to its pre-recession level (and possibly surpassing it when firms make their final estimates). This is a remarkable achievement for an industry widely-perceived as being in its death throes. The level of investment in 2012 is the fourth highest on record, surpassed only during the peak of the ICT boom in the late1990s.

So where is this investment in factories going? Primary metals posted the highest level, at $4.1 billion. But generally, the contribution of resource-based manufacturers to investment growth was only half of its contribution in 2011, reflecting a drop in petroleum refining at its lowest level in over a decade (partly because major investments in expanding capacity last year were completed), cutbacks in non-metalllic minerals and lingering weakness in wood and paper. Instead, investment reached record levels in metal fabricating and machinery, both of which approached the $1 billion level, as well as food. Transportation equipment, which is mostly autos, is keeping outlays at about $2 billion for the fourth straight year, half its pre-crisis level. Almost all this investment in auto plants is in machinery and equipment, not surprising given the excess capacity in this industry. More generally, for all manufacturers, three-quarters of investment is going into productivity-enhancing machinery and equipment.

Quebec and Ontario shifting away from factory-based economies to power and mining

Regionally, all the major provinces participated about equally in the resurgence of business investment over the last two years, with gains of about 27% in both BC and Alberta and about 20% in both Ontario and Quebec. Alberta’s growth was of course dominated by oil and gas. BC was able to keep up thanks to its natural gas in northeastern BC as well as a major refining project. Investment in Quebec was led by a spectacular 62% jump in mining investment which, at $4.4 billion, almost equalled all investment in manufacturing. In Quebec, investment in utilities and mining combined has surpassed manufacturing since 2005: capital spending for the two is projected at $10.5 billion in 2012, over twice the $5.0 billion in manufacturing. Ontario has started to follow this pattern of utilities and mining overshadowing its manufacturing sector since 2009: in 2012, utilities and mining investment totaled $8.0 billion, versus $7.5 billion in manufacturing. Mostly this new industrial pattern in investment reflects the strength in mining and utilities since, as noted above, manufacturing investment has returned to normal levels. However, there are wide regional variations for the completeness of the recovery of manufacturing investment: the Atlantic region, Quebec, Manitoba, Saskatchewan and BC all have exceeded pre-recession levels, while Ontario and Alberta are well below (mostly due to autos and oil refining, respectively).

Why business investment matters

Business investment is the key to understanding the evolution of the macroeconomy for a number of reasons. As noted above, it is the key determinant of what Canada’s industrial structure will look like tomorrow. As I wrote in a paper in 2010, investment patterns in the 1990s were a very accurate guide to which manufacturers prospered and which struggled in the 2000s—and that was before there was any hint of the appreciation of the loonie. The link to the paper is provided here http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/11-010-x/2011003/part-partie3-eng.htm.

Second, business investment has the most predictable cyclical properties of any component of expenditure. While household spending or exports can turn on a dime, cycles in business investment tend to be very long and consistent. Once firms decide to cut investment, it has fallen by almost exactly 20% in each of the last three recessions. But once firms decide to spend, investment outlays then rise for about five years, on average. This lends a great deal of stability and predictability to the economy.

Third, the willingness of firms to invest is a good barometer of their willingness to hire, and of course the two decisions are inter-related. As the graph below shows, there is a close correlation between the investment rate (the share of business investment in GDP) and the unemployment rate. Since jobs and unemployment in turn are an important determinant of consumer spending, this amplifies investment’s role in driving the overall economy.

And finally, investment is the key link between the real and financial sectors of the economy. The decision to invest implies a decision about how to deploy financial assets and alter liabilities.

In the aftermath of the recent financial crisis it is trendy to quote Hyman Minsky’s famous observation that “stability is destabilizing”: the idea that what economists call The Great Moderation of the macroeconomyin the 1990s and early 2000 laid the foundation for The Great Contraction. But it is worth recalling the full quote: “Stability is destabilizing, not initially to a recession but first to an expansion of investment.” The primacy of investment in Minsky’s theories of the business cycle is clear “Investment is the essential determinant of the path of a capitalist economy: the government budget, the behavior of consumption, and the path of money wages are secondary.”[4] If you agree with Minsky, then Canada is well-positioned for growth for the next few years. But before you get too carried away with optimism, remember another of his observations “success breeds a disregard of the possibility of failure.”

[1] Business investment is calculated as total investment in all sectors, excluding housing, public administration, education and health. This is quite close to the definition used by the National Accounts, apart from some minor adjustments for areas like water utilities, a level of detail which is not available on Cansim.

[2] These results are not adjusted for price changes, but prices for business investment fell slightly in both 2010 and 2011, so there is a good chance that the constant dollar results could match or exceed the increase in nominal spending.

[3] In the overview section, I include primary metals in energy and mining. But during the detailed analysis of mining and manufacturing, to avoid confusion with the traditional classifications, I leave primary metals in manufacturing.

[4] Hyman Minsky, Stabilizing an Unstable Economy. McGraw Hill, p 191.